Bolt Fatigue and a Bolt's Thread Root

Most Engineers will likely come across a fatigue failure at some time in their career. Fatigue is the progressive cracking of a material due to repeated loading and unloading cycles. For fatigue to occur, there must be a repeated change in the loading condition and subsequently, the stress condition. No stress change, no fatigue. A fatigue crack in a part will normally initiate at the location on the part with the highest stress condition. For bolts, this location is usually at the root of the thread nearest the nut-to-joint interface. It can take thousands, or even millions of load cycles for the crack to propagate through the bolt. The thread root is the bottom of the thread and is the region where the stress is significantly greater than the surrounding region. Such a feature is referred to as a stress concentration. Essentially, other factors being the same, the smaller the stress concentration, the better is the fatigue life.

Most Engineers will likely come across a fatigue failure at some time in their career. Fatigue is the progressive cracking of a material due to repeated loading and unloading cycles. For fatigue to occur, there must be a repeated change in the loading condition and subsequently, the stress condition. No stress change, no fatigue. A fatigue crack in a part will normally initiate at the location on the part with the highest stress condition. For bolts, this location is usually at the root of the thread nearest the nut-to-joint interface. It can take thousands, or even millions of load cycles for the crack to propagate through the bolt. The thread root is the bottom of the thread and is the region where the stress is significantly greater than the surrounding region. Such a feature is referred to as a stress concentration. Essentially, other factors being the same, the smaller the stress concentration, the better is the fatigue life.

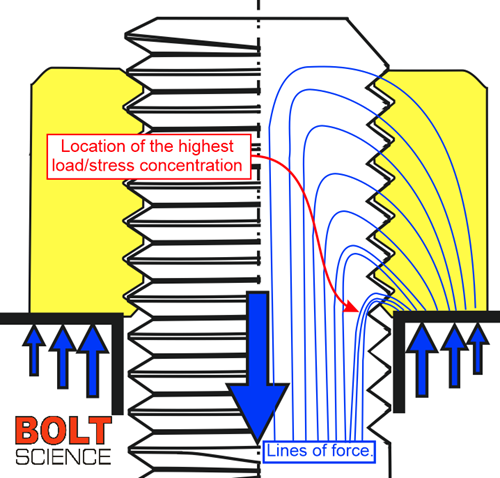

When bolts fail due to fatigue it is usually in the first thread root next to the nut-to-joint interface. The fracture surface of a bolt that failed due to fatigue is shown in the photograph. The reason why failure occurs here and not in another thread root is that the loading is focused on this region. The load must pass between the joint, the nut and into the bolt. Since the loading will take the stiffest path, more loading passes through the first thread in the nut rather than a thread further back. The loading passes between the load flanks of the nut and bolt. The load path is illustrated in the image shown. The loading is more focused on the first thread and hence so is the stress. The stress concentration in the thread root region is between 4 and 6 depending upon the pitch and diameter of the thread. (This means that the stress can be up to 4 to 6 times the stress in the central section of the bolt thread.)

There are two main reasons why the root of the thread is rounded. Firstly, the rounding reduces the stress concentration and hence facilitates fatigue resistance. Secondly, since most bolt threads are rolled rather than cut, the rounding increases the life of the dies used in the rolling process. It is advised that the thread root is fully rounded, but a partial rounding is allowable. These two types of thread root profile are illustrated in the image.

There are two main reasons why the root of the thread is rounded. Firstly, the rounding reduces the stress concentration and hence facilitates fatigue resistance. Secondly, since most bolt threads are rolled rather than cut, the rounding increases the life of the dies used in the rolling process. It is advised that the thread root is fully rounded, but a partial rounding is allowable. These two types of thread root profile are illustrated in the image.

Tolerances are placed on the root radii which for metric threads the radius must be between 0.125p to 0.144p where p is the thread pitch. Hence for an M6 coarse thread whose pitch is 1 mm, the root radii must be between 0.125 mm to 0.144 mm. Limiting the radii to a minimum value, limits the stress concentration present.

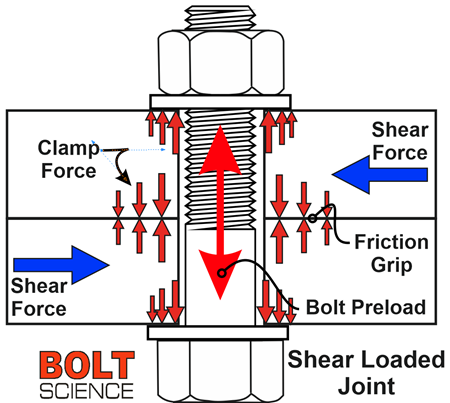

The type of loading sustained by the joint influences the bolt's load response. The majority of bolted joints that are shear loaded have clearance holes. That is the hole is larger than the bolt thread such that there is a radial gap present between the bolt and the hole. Such joints rely upon the clamp force generated by tightening the bolt to transmit any shear by friction between the joint plates. This is as opposed to shear being transmitted between the plates through the bolt shank. Such joints are referred to as friction grip joints. With such a joint, if designed and assembled correctly, the bolt will not experience a load change when the shear force is applied. Accordingly, if there is no load change, there is no stress change in the bolt and hence no fatigue. If, however, the bolt is not tightened sufficiently, or the interface friction is low or the loading too high, the friction grip can be overcome so that the joint slips. When the interface slips, at first the bolt head and nut face will still have some friction grip present. Such friction grip will resist the joint movement resulting in the bolt sustaining a bending stress. Fatigue failure in the thread root due to a shear loaded joint's friction grip being overcome is a common, or even the commonest, cause of bolt fatigue failure.

With an axially loaded preloaded joint, the bolt does not sustain the full magnitude of the applied loading; most of the loading reduces the clamp force. There is a small proportion of the loading, typically between 5% to 20%, that will be sustained by the bolt. If the axial loading varies, this will cause the stress sustained at the thread root to vary and hence, potentially, sustain fatigue. With a properly designed joint, the alternating stress sustained under axial loading is kept below the fatigue endurance limit of the bolt. The endurance limit is the value of alternating stress that will provide an 'infinite' life. If the alternating stress is below the endurance limit, fatigue failure wouldn't be anticipated for the life of the product. Stresses larger than the endurance limit will result in a fatigue failure occurring in a finite number of load cycles.

With an axially loaded preloaded joint, the bolt does not sustain the full magnitude of the applied loading; most of the loading reduces the clamp force. There is a small proportion of the loading, typically between 5% to 20%, that will be sustained by the bolt. If the axial loading varies, this will cause the stress sustained at the thread root to vary and hence, potentially, sustain fatigue. With a properly designed joint, the alternating stress sustained under axial loading is kept below the fatigue endurance limit of the bolt. The endurance limit is the value of alternating stress that will provide an 'infinite' life. If the alternating stress is below the endurance limit, fatigue failure wouldn't be anticipated for the life of the product. Stresses larger than the endurance limit will result in a fatigue failure occurring in a finite number of load cycles.

With an axially loaded joint, if the bolt was not tightened sufficiently, or the axial loading too high, the clamp force acting on the interface can be overcome. This results in a gap occurring in the joint interface, referred to as joint separation. The bolt than would sustain the full magnitude of the applied loading with potentially a large alternating stress in the thread root. Again, this is a common cause of fatigue failure.

In general, for both shear and axially loaded joints, increasing the bolt preload will reduce the risk of fatigue failure occurring. There are obvious limits to how much a bolt can be tightened. Checking that the bolt had been tightened correctly is one of the first steps in a fatigue investigation. If the tightening was as specified, frequently, increasing the tightening torque and increasing the bolt strength (say from a property class 8.8 to a 10.9) is often second on the list when seeking to resolve a fatigue issue.

For reference, note that the force-flow lines shown in the nut image and their effect on fatigue originates from work in the 1930's by H. Wiegand in Germany. His work is reported in Perterson's Stress Concentration Factors, second edition by Walter D. Pilkey.

Numbers can be put to the above in what is referred to as a joint analysis. The BOLTCALC program can perform such an analysis and complete a design check as to whether fatigue is a possibility, or not.

With an axially loaded joint, if the bolt was not tightened sufficiently, or the axial loading too high, the clamp force acting on the interface can be overcome. This results in a gap occurring in the joint interface, referred to as joint separation. The bolt than would sustain the full magnitude of the applied loading with potentially a large alternating stress in the thread root. Again, this is a common cause of fatigue failure.

In general, for both shear and axially loaded joints, increasing the bolt preload will reduce the risk of fatigue failure occurring. There are obvious limits to how much a bolt can be tightened. Checking that the bolt had been tightened correctly is one of the first steps in a fatigue investigation. If the tightening was as specified, frequently, increasing the tightening torque and increasing the bolt strength (say from a property class 8.8 to a 10.9) is often second on the list when seeking to resolve a fatigue issue.

For reference, note that the force-flow lines shown in the nut image and their effect on fatigue originates from work in the 1930's by H. Wiegand in Germany. His work is reported in Perterson's Stress Concentration Factors, second edition by Walter D. Pilkey.

Numbers can be put to the above in what is referred to as a joint analysis. The BOLTCALC program can perform such an analysis and complete a design check as to whether fatigue is a possibility, or not.

To assist the Engineer in overcoming the problems associated with the use of threaded fasteners and bolted joints, Bolt Science has developed a number of computer programs. These programs are designed to be easy to use so that an engineer without detailed knowledge in this field can solve problems related to this subject. Training on bolting is also available from Bolt Science, for further details on the training that we can provide for Engineers, follow this link.

Social Media Links

Instagram

Linkedin

Twitter

|